I’m fascinated by hops.

That can surprise people who know me as a brewer—in my homebrewing circles, I’m notorious for rarely brewing hop-forward styles. That’s not because I don’t appreciate hops, though—far from it. In fact, one reason I lean more into malt- and yeast-driven flavor profiles is that hops are such a black box.

Let me share a quick anecdote to highlight what I mean.

If you ask anyone about what makes a great Czech-style pale lager, they’ll probably tell you that it’s the smell and taste of Saaz. Shovel it in—you can’t get enough of it. But that’s just it: I was shoveling it in, and I still wasn’t getting a real, palpable expression of that Saaz flavor. Another ounce. And another. And another. They were solid pilsners, don’t get me wrong, but they were clearly lacking that Saaz flavor.

So, one day I decide to go 50/50, Saaz and Styrian Goldings, and voilà—huge “Saaz” flavor. Why?

The answer is simple, even if the conclusion is frustrating: Hops are complicated. They’re a lot more complex than the overly simplistic metrics we tend to use to describe them. (“What’s an alpha acid?”) They’re even more complex than the more detailed metrics we have available. (“What are the beta acid and cohumulone and myrcene levels?”) And they’re light-years beyond the high-level descriptors we tend to hang on them. (“Tropical, spicy, floral”—seriously? Is that the best we’ve got?)

So, today we’re going to dig deeper—deep enough to strike hop oil. It would be too much to promise that by the end of this piece, you’ll be able to add linalool and 3-sulfanylhexan-1-ol to get the exact flavor you want, the way you might add black pepper and garlic to a good steak. However, to quote the great golf teacher Harvey Penick, “take dead aim,” and your results will nearly always improve.

So, first things first: What’s in a hop?

The Oils Are Essential

A lot goes into a hop cone and, as a matter of simple fact, we actually do taste a lot of it.

The leaves, bracts, bracteoles—the very plant matter within it—all contribute something to the flavor. Consider how the top of a strawberry tastes green and bitter, even while the rest of the flesh tastes more like what we usually associate with “strawberry flavor.”

Yet there’s a very, very small percentage of the hop cone that’s doing a lot of the lifting: its oils. Found in the cone’s lupulin glands, the hop’s essential oils are responsible for the unique aroma and flavor profiles that wind up in beer. The brewing process extracts those oils and their volatile compounds, typically during mashing, boiling, whirlpooling, and/or dry hopping.

Those oils play a crucial role in shaping the overall sensory experience of beer, contributing to its aroma, flavor, and even its mouthfeel. As they combine and interact with the wort before, during, and after the brewing process, we get what we often grossly oversimplify as a beer’s “hop flavor and aroma.”

In the world of hop oils, each compound brings its own signature to a beer’s aroma and flavor. You’ll often find these oils listed in a hop’s varietal description—as a percentage of the oils present—when you buy them:

- Myrcene, the big hitter, offers a resinous, green profile, lending that classic green, “dank,” almost sticky sensation.

- Humulene provides the piney, woodsy backbone, especially in Noble hops, contributing a spicy, herbal character.

- Caryophyllene—my personal favorite—also has that woody edge but with a bit more emphasis on earthy.

- Farnesene throws in a more delicate floral note, balancing the heavier aromas.

- Linalool is another floral player, often leaning into orange blossom and brightening things up.

- Geraniol, the rose-like floral oil, sweetens the profile with hints of pollen and perfume.

So, while hop oils might not always grab the spotlight, they’re the unseen architects that shape many of our favorite beers, whether they’re resinous, floral, earthy, fruity, tropical, spicy, sweet, or bitter. And we can make use of them: Comparing the percentage of each of these oils in a given hop variety, crop, or bale can give us a bit more control over the finished beer.

Besides, you’ll sound a lot hipper among fellow brewers when comparing the caryophyllene levels, let’s say, in Northern Brewer and First Gold hops.

Ready to Drill Deeper?

For more insights into making the most of those oils, I reached out to Scott Janish—author of The New IPA: Scientific Guide to Hop Aroma and Flavor, cofounder of Sapwood Cellars in Columbia, Maryland, and someone whose input I’ve been leaning on for years in my own brewing.

Besides providing guidance on the composition and utility of the oils mentioned above, Janish also gets into the weeds (so to speak) on even more esoteric compounds and combinations. So, let’s talk thiols.

Thiols, generally speaking, are sulfurous compounds with strong flavor profiles that are found in hops and their oils—though they make up a tiny fraction of those oils, which are already a tiny fraction of the hop. In short, once unlocked, thiols can be powerful.

“Free hop-derived thiols can significantly impact beer aroma, even at very low concentrations,” Janish says, “contributing intense fruity notes like grapefruit, passion fruit, and black currant.” Yeast labs have been developing bioengineered strains that free up more of those thiols, which “can dominate beer … compared to traditional dry hopping,” he says. However, “because their taste threshold is so low, even small concentrations can contribute to the beer.”

Specific thiol compounds are often responsible for highly specific aromas or flavors. Here are a handful of the better-known ones in hops:

- 3SH (3-sulfanyl-hexanol) brings notes of grapefruit, passion fruit, rhubarb, or gooseberry.

- 4SMP (4-sulfanyl-4-methylpentan-2-one) contributes black currant as well as “catty” aromas.

- 3SHA (3-sulfanylhexyl acetate) can offer notes of passion fruit or guava.

- 3S4MP (3-sulfanyl-4-methylpentan-1-ol) brings vinous or grape-like flavors, most famously in Nelson Sauvin hops.

- 2MIB (2-methylbutyl isobutyrate) produces apricot-like flavors.

While hop vendors often list the typical oil percentages with their varieties, not many explicitly list the thiol levels. However, some are beginning to note which varieties are especially high in thiols.

Also, besides the thiol-enhanced yeast strains, there are precursor products such as Phantasm—made not from hops, but from thiol-rich grape skins—as well as hop products enriched with those precursors.

While it’s useful to know about thiols and those products, here’s a word of warning: Thiols can be potent, and their expression can vary significantly depending on the beer, how it was brewed, and the drinker. One person’s pine forest or passion fruit can easily be another person’s kitty-litter box or diesel can.

Building a Well-Oiled Machine

When it comes to getting the most out of our hops, there are a couple of ways to tackle the challenge: by using a general approach or by following some specific-use cases. If you’re systematic about it, either way can inform your recipe development or personal R&D.

Starting with the general approach: Depending on how long you’ve been at it, you may or may not have come of brewing age at a time when 60-minute additions were for bittering, 30-minute additions were for flavor, and 10-minute (or later) additions were for aroma. You can make great beer with that approach, obviously, but it basically ignores the physical reality of hops oils: They tend to be highly volatile at temperatures at or even below boiling temperature.

So, given that reality, please allow me to impress upon you one simple truth: In the boil, they are all bittering hops.

Yes, you might preserve some hop flavor and aroma by adding hops late in the boil. However, it’s always going to be less than if you adopt the “don’t boil them at all” approach that’s become increasingly common in the world of IPA. Need some IBUs via isomerized alpha-acid extraction? By all means, then, toss them in the boil. If you want to maximize the aroma and flavor, however, keep them away from the bubbling cauldron.

In a blog post that changed my life—or at least my beer recipes—Janish notes that up to 80 percent of linalool will boil off in just five minutes in the wort. Most essential oils in hops have a boiling point either at or below 212°F (100°C). I repeat: In the boil, they’re all bittering hops.

That’s where the whirlpool comes in. We want some heat to aid in extracting the oils, so just dumping them into cold wort isn’t necessarily the best. For many modern brewers, whirlpooling at about 180°F (82°C) has become the answer.

Generally, Janish says, monoterpenes such as linalool and geraniol are relatively easy to get into the beer “and have good staying power once extracted.” Myrcene, on the other hand, can be more difficult to hang on to in large quantities—although “more viscous hazy IPAs have been found to retain more of these compounds than drier West Coast IPAs,” he says.

Cold Side, Hot Side, and Synergy

Dry hopping can also be useful for preserving some of these oils, though the cooler temperatures tend to limit their extraction potential.

True, the oils aren’t going to boil away, but they aren’t being pulled from the pellet or flower all that efficiently, either. However, your more fragile oils and thiols are going to survive here.

When it comes to hop oils, the primary consideration when dry hopping isn’t so much the temperature but the time: If you’re comfortable with the chance of biotransformation—or actively seeking it out, to get some unique aroma compounds—then go ahead and add your hops at primary fermentation. If your goal is to get what you can from the hops themselves, then dry hopping in secondary—possibly after cold crashing—is preferable.

Also, it’s wise to be conscious of what else you’re getting out of those dry hops because some of that can interact with the flavors you’re hoping to get from the oils. Here are a couple things to keep in mind:

- First, you may be extracting flavor-altering phenols. While we often (correctly) think of phenols as a fermentation product, they can also be hop-derived—and those peppery, perfumy compounds can really out-shout the more subtle flavors from your oils.

- Second, while you don’t need to worry about isomerizing alpha acids when dry hopping—and they’re only of limited concern in the whirlpool—beta acids are still coming to the party. As they (and the beer) oxidize, their bitterness begins to come to the fore, and not necessarily in a way you’d like.

As with every ingredient, be intentional: Use what you need and want, leave out what you don’t. Ultimately, this is about synergy.

“All hop compounds can play a role in beer flavor and aroma,” Janish says, “which is partly why I focus on maximizing the compounds introduced into the fermentor.”

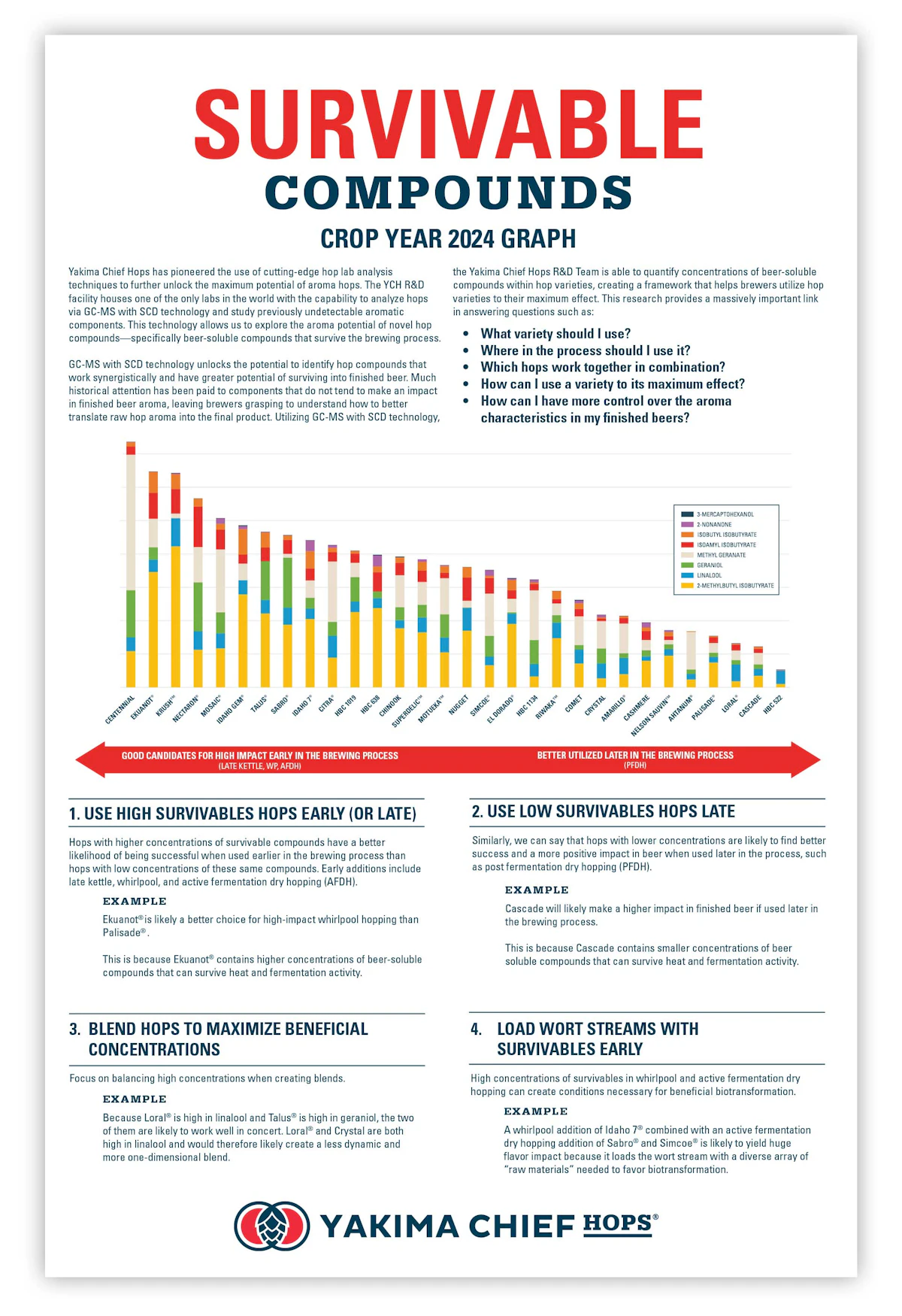

This is where it can help to pay attention to “survivables.” These are the aroma compounds best able to endure a late-boil addition, the whirlpool, and active-fermentation dry hopping. Certain hops—such as Centennial, Ekuanot, and Idaho 7—are richer in those compounds. Going with those sorts of hops at, say, two pounds per barrel—roughly an ounce per gallon, or 7.5 grams per liter—you can achieve a “layering effect” to help push a more hop-saturated flavor. To build on that, you may want to reserve varieties lower in survivables—such as Amarillo, Cascade, Willamette—as dry hops on the cold side.

Once you really dive into the compounds you like, which varieties have them, and when best to add them, there are other ways—many still waiting to be discovered—to get more from them than the sum of their parts.

“There is also a synergistic relationship between these compounds that can enhance one another,” Janish says. “For example, the presence of 3S4MP can make the fruity, apricot-like notes of 2MIB more pronounced, even when 2MIB is present at levels below its typical flavor threshold.”

Like so much else in brewing, it’s usually necessary to try, then trust—but you can still stack the deck in your favor.

More Discoveries Await

There’s no doubt about it: Hops can be challenging. They’re variable and complex, so there aren’t really any hard-and-fast rules to follow that can guarantee a certain outcome.

“There are definitely still unknowns when it comes to hop varieties and what makes them unique,” Janish says. “A prime example is one of my favorite hops, Riwaka. It’s one of the most aggressive and stubborn hops—even small amounts added to the kettle will still be detectable in the finished product.”

At Sapwood Cellars, he says, they brewed a collab beer with Fidens of Albany, New York. Called Hidden Thiols, it was an all-Riwaka double IPA.

“What thiol—like 3S4MP in Nelson—makes Riwaka truly distinctive?” Janish says. “I’m not sure! … But whatever it is, I really enjoy it.”

It’s that degree of serendipitous uncertainty that makes hopping so much fun, despite its complexity and challenges. Having a clearer sense of the oils and thiols in your favorite hops—and knowing how best to get them into your beer and having the flexibility to roll with the unknown and unpredictable—will help you, as a brewer, keep things on the fun side of that ledger.

Meanwhile, there’s still plenty of challenge there to keep us intellectually engaged on this topic into the foreseeable future. After all: If we didn’t have to work for it, wouldn’t beer be a lot less interesting?